AN ACCOUNT OF LIFE ON MAMMON

Editor’s Note: Ezra Lilly, 62, general manager of the Mammon Intergalactic Hotel in Hilltown, gives an account of life on his planet. Ezra immigrated to Mammon with his mother, Rose, a mining engineer, at age four. He grew up in remote mining camps all over the planet and during this time developed a lasting appreciation for the planet’s natural beauty. He set out for Hilltown at age eighteen to make his fortune, and, after taking a stab at a variety of consumer service businesses, settled on hotel management as a career. As manager of Mammon’s largest hotel, Ezra has developed a side business as an art dealer, handling both Human and non-Human art forms. He has edited several books on art and written an entertaining volume about backpacking on Mammon.

My mother is one of those workaholics who can’t live with a career and a husband. Before I turned four, she terminated her marriage contract, took custody of me, and signed up with Mammon Mining Company for a stint as a mining engineer. Her divorce had left deep wounds, and she thought a change of scene might make her forget the unpleasantness. Like most immigrants of the day, Mom intended to return to Earth after making a comfortable nest egg, but like most immigrants, she remains on Mammon to this day. She still works 40 or 50 hours per week and has no more desire to live on Earth than on Ignati.

My childhood memories of the original Hilltown recall a haphazard cluster of structures on grassy hills overlooking the sea. Back then, MMC had no time for landscaping the camp, and the great bustle of activity trampled the grass into dust that flew in all directions as the levitrucks took off and landed.

Mother spent eight to twelve hours a day, six or seven days a week, at the mine. I passed the time in an ad hoc day care center run by the spouses of some miners who also had small children. My days were an informal mixture of play, games, and lessons. What our teachers lacked in skill and polish, they more than compensated for in hard work and enthusiasm. Most of the lessons came off computer files, but there weren’t enough terminals for every child. Undaunted, the teachers found ingenious ways for all of us to participate, like having us write answers to questions in the dirt with pointed sticks.

Despite her grueling schedule, Mother always took time at the end of the day to sit alone with me and talk. She always asked me what I had done and what I had learned. If I said I learned nothing, she would scold me firmly, but kindly, and tell me that all of my life I should learn at least one new thing every day. On her days off, Mother usually managed to commandeer a truck to take me away from Hilltown. Some days we went to the shore of Fortune Bay and poked among the tidepools or walked along the great sandy beaches. On others we headed for the nearby ridge of low mountains to fish in the tiny streams and lakes or to hike amidst the thick forests. Some days when Mom didn’t feel like walking, we glided silently in the levitruck, just above the treetops, looking for wild animals. I liked this best, for it seemed as exciting as a hunt, yet I knew that with the flick of the control lever we could whisk into the air, out of danger. Once we stalked within five meters of a great masher beast, a large, hoofed creature with a mouthful of terrible teeth, as it stood gorging itself on its prey.

By the time I turned ten, the success of the Hilltown mine had proven that mining on Mammon was profitable. From then-on, Mammon-Mining Company wasted little time in expanding its operations to other mine sites, and they called upon my mother to help. Mother’s technical specialty lay in the startup of laser-fusion excited, trispectrum, automining equipment, which employs elements from the most sophisticated of Human technologies. This equipment effectively strips the soil and rock of the oxides of desired elements, then returns the remainder to a nearly natural state. Starting these systems up takes as much art as science, since numerous factors influence the stability and efficiency of the process, including the hardness and composition of the areas being mined, the mix of rare earths being separated, the climate and the construction of the equipment itself. Getting a new mine operational took anywhere from eighteen months to three years after the equipment arrived. Once the equipment began operating satisfactorily, Mother moved on to a new site and a new nest of technical problems.

Hilltown, the home of my childhood, didn’t seem like much until we moved away. The town formed the nucleus of the planet. What little farming, manufacturing, and commerce existed on Mammon happened there. Other mine sites looked like remote outposts in comparison, and my lifestyle became more solitary after leaving Hilltown. During the next eight years, Mother and I lived at four different mining camps. Though each had its unique features, many aspects of life in the camps were the same.

When we arrived at each mine site, it swarmed with hundreds of people. Unfortunately for me, most served as temporary contract laborers who brought no families and left within six months of our arrival. Only the permanent operating personnel and a few construction supervisors had their children with them, so the entire teenage population of each mine usually numbered less than thirty. Parents who didn’t work at the mines took turns caring for little children, just as they had done in Hilltown’s early years. After I turned twelve, Mother no longer felt that I needed such care and let me shift for myself during the day while she worked.

Smaller mine communities didn’t have schools, so most parents had to rely solely on computer education for their children. Mother values education highly, and so she got me the best education terminal money could buy. Before it arrived, she began selecting a curriculum of study that included heavy doses of science and business, as well as language, Earth history, and mathematics?

In my years at the camps, my computer teacher became the most important possession I owned. It had an enormous holographic display, nearly a meter square and accepted both voice, fast-tran, and long-form keyboard input as well as telepathic feedback. The lessons came via satellite from Hilltown’s library, and though I know each one was just a complex computer program, they seemed more real than that. As I sat before the screen each day, I left the real world of the camp behind me. Geography lessons took me soaring over the face of Mammon, peering down with eagle’s vision. When studying astronomy I zoomed into space past brilliant suns and spinning planets to look into the awful maw of black holes that gobble up all but the most intense forms of energy. Studying Earth’s history carried me across light years to look upon the battlefields, castles, and pyramids of our mother planet’s once great nations.

As I traveled, the teacher’s soothing voice explained the things I saw, then asked me questions about them. If I gave the right answer, it praised me and we went on to something new, but when I made mistakes, we reviewed to see where I went wrong. At times I saw reenactments of great events in history. Though somewhere in the back of my mind I knew I wasn’t really watching Bonaparte inspire his troops before Waterloo or Armstrong stepping on to the moon, I felt as though I lived through these events and knew why people had struggled so hard to do the things that made our history.

Even the abstractions of mathematics came to life on the screen as I manipulated equations and geometric forms against the green backdrop. The teacher always seemed to know when I had missed some point and went back to explain and illustrate again. When studying binary mathematics, I loved to watch the teacher break down the most complex sentence I could concoct to the elemental ones and zeroes of all knowledge right before my eyes. I rarely desired to play hookey from my lessons, but if I had, Mother would have known. Each evening she looked at my progress score and, on rare occasions when it seemed low, she talked to me about things the teacher couldn’t explain.

The teacher wouldn’t continue my lessons more than eight hours a day, and Mother didn’t let me watch more than two hours of shows after that. She felt that I should spend some time outside each day, getting exercise and associating with people my own age. During these hours I did a lot of hiking and exploring and learned to appreciate the wondrous natural beauty of our planet.

Most outsiders think of Mammon as a desolate, desert world, but though the terrible wastes of the Great Khalid desert dominate its surface, Mammon possesses much territory as beautiful as can be found on any world. Our second home at Blackrock mine lay at the northern edge of a rich, rainswept plain of tall forest. Enormous trees rising up to sixty meters formed a canopy over thousands of interesting plant and animal life forms. Tiny climbing creatures with hand-like claws scamper among the treetops and toss bits of bark and seed cones at intruders walking below.

Our third home at the Oasis mine of the western Plat region nestled in a fertile river valley of temperate climate. The wind sweeps the Plat night and day, every day of the year. When we first arrived, we thought it would drive us mad, but after a while we learned to tolerate it. The region’s trees all bend eastward before the howling wind that feeds the great furnace of the Khalid to the west. Mother didn’t like the Plat and worked furiously to get the Oasis project on line so we could leave the infernal wind.

The very day the superintendent accepted the automining equipment, Mother arranged for us to hitch a ride back to Hilltown on a returning freight caravan crossing the Khalid desert. In those days, heavy duty antigrav trucks had a top speed of just 300 kilometers per hour. Ideally, vehicles crossing the Khalid prefer to do so at night because a breakdown during the midday heat would be fatal to the passengers. Unfortunately the desert measures 9,000 kilometers wide and can’t be crossed in one night.

We left Oasis at dusk riding in the lead truck’s cab at the head of a long string of automated vehicles, which followed us. Overhead the sky glowed with the last rays of twilight, while below an inky expanse swept to a distant horizon. I slept most of the night, and as dawn broke I looked out at an ocean of sand extending as far as I could see in all directions. The mountains of the Plat had passed out of view behind us, and nothing lay ahead but white expanse. As the temperature climbed, so did we until by midday we flew at almost 15,000 meters, breathing supplemental oxygen from masks. Despite the high altitude, the cab’s temperature climbed to 30° C. The dry air parched our throats and skin, and though we sipped water constantly, it brought little relief. As we traveled, some geographical features came into view: an occasional ridge of mountains or a grey patch that Mom said might be gravel instead of sand. Yet nowhere did we see a drop of water, a speck of vegetation, or any living thing. Mother said no geological evidence of water had ever been found.

Throughout the day the sky never turned blue, but remained dawn pink. Though no water clouds appeared, we could see great dust storms rising thousands of meters into the air, some as high as we were flying. They appeared as opaque, shapeless masses, blocking all light and turning the sky near them a deeper pink. We continued to travel throughout the night, gradually descending to eliminate the need for oxygen. As dawn broke, blue sky appeared, and we saw vegetation below, indicating the desert lay behind us.

We spent the next month in Hilltown while the company’s planning staff briefed Mother for her new assignment at the Tobar mine. Hilltown had more than doubled in size since we left for Blackrock four years before. The residents bubbled with ambitious plans for moving the city center so that future growth could be planned instead of haphazard. Everyone we met exuded enthusiasm for the project. They felt that someday Hilltown would become the cultural center for an important, wealthy planet instead of just a staging ground for a gold rush expedition.

After we left for Tobar, I soon forgot the future of Hilltown. Tucked into the foothills of a stunning range of snowcapped mountains, the mine camp overlooks a sky blue gulf, lined with broad beaches of sugar-white sand. The idyllic period at Tobar seemed the happiest in my short life. I spent most days at the beach, had my first torrid romance with another miner’s daughter, and began to think of the world as my oyster when Mother got promoted.

The promotion offered a tremendous boost to Mom’s career, and I couldn’t bring myself to say anything bad about it. She jumped from field engineering specialist to production superintendent. Unfortunately, the job was at the Port Node mine in the perennially frozen northern wastes. My mood reached a low point as we landed on that bleak plain littered with scruffy mounds of snow extending to an infinite horizon. The timing, a month before my eighteenth birthday, worked out well since I was preparing for my comprehensive exams, and the forbidding landscape made staying inside and studying even more attractive. I turned eighteen, the legal age on Mammon, and finished my formal education. Mother offered to get me a job at the mine or to send me to the University at Hilltown. In those days, the U of H offered little except courses that prepared people for mine-related industry, and I had long ago decided that the mining life was not for me. I wanted to live in a city, enjoying the benefits of luxury. I couldn’t stand the thought of spending my days around a dusty, open pit mine, getting rich, but having nothing to spend it on. Indeed, it seemed to me that Mammonites would soon insist on having comforts and luxuries in exchange for the vast sums they were accumulating in banks. I determined then to get into the business of supplying these needs and packed up my belongings for a move to Hilltown. Mother took this news in her usual gruff but good-natured way.

“It’s your life, son,” she said as we parted. “I can’t see what sort of career you’re going to find in that carnival town! But, nobody could tell me how to run my life, so I can’t expect to tell you. Whatever you do, do it well.”

In the three years since my last visit, Hilltown had changed a great deal. The citizens had approved the development plan for the new city and several major buildings had sprung up. All of the major spires from the old city had been relocated in the new area with more space and landscaping around them. The plan called for the original town to be left largely as it was, a collection of low structures containing bars, restaurants, cafes, brothels, small stores, and an assortment of small hotels. A high-speed guideway then under construction would soon connect the new town with the old.

Since so many people had headed for higher paying jobs in the new town center, a great many jobs remained to be filled in the old city. I had some experience as a helper in Tobar’s camp kitchen; so I started out as an assistant cook in a tiny, classy restaurant. An irascible old Frenchman named Henri Legasse runs the Rive Gauche, and it remains one of Hilltown’s finest gourmet eating places to this day. Though foodmasters, autoselectors, and kitchen robots alleviate much of the drudgery of preparing meals at home, Henri taught me the importance of Human dexterity and skill in serving truly fine food. Only Human hands can properly prepare a salad, a pate, or a pastry as pleasing to the eye as to the palate. Only the Human eye can tell when an omelette has reached the instant of perfection, or when a roue has thickened to ideal consistency. Only the Human nose and tongue can correct the seasoning just the right amount to turn a good sauce into a great one. In his abrupt, arrogant way, Henri must have liked me, for whenever I mastered one task and asked to learn another, he agreed. In the ten years I worked at the Rive Gauche, I learned to prepare dishes from the first course through dessert.

Though Henri ranks as the greatest chef I have ever met, he was an awful businessman. Often I had to help out with ordering supplies or computing the payroll. Once a year I made a dreaded trip to the accountant’s office to try to sort out Henri’s hopelessly scrambled financial records. I enjoyed learning as much as I could about the business, for my ambition then was to own a restaurant, not just to work in one.

After nine years in the kitchen, I made the unprecedented request to work up front as a waiter. To everyone’s surprise, Henri agreed, and I was fitted out in formal attire to serve the public. The kitchen and dining room stood in such striking contrast to each other that they hardly seemed part of the same place. The kitchen gleamed with pure white steroglass, stainless alloy, and gold. At both ends, a wall of ovens cycled food continuously from beginning microwave cooking to final browning with long-wave heat. At work stations along each wall and around a center island stood the intricate chopping, grating, and purging machines, and the cookers for steaming, sauteeing, and boiling The clatter of dishes, the whoosh of ventilators, and the constant chatter of the cooks filled the air.

Stepping through the short, sound-blocking corridor from the kitchen to the dining room brought a change as abrupt as a warp through space. Natural hardwood paneling covered the walls and thick carpet lay underfoot. Padded leather chairs surrounded linen-covered tables and formally dressed waiters moved like ghosts between them. White noise absorbers soaked up sound to create church-like silence. Here gourmets from all over the planet came to relax and worship the art of fine cooking. Though not as demanding as the kitchen, serving revealed to me a completely different dimension of the restaurant. Unlike the robot servants in cheaper restaurants, subtle changes in the conduct of a Human waiter influenced the guest’s perceptions of the meal.

One of our regular customers was a big, jovial woman whose good-natured manner thinly masked an iron will. I liked her because she reminded me of my mother. One night, after a little too much wine, she remarked that she’d better keep me away from her girls or they’d be giving away the merchandise. After that I inquired about her and discovered she was Bertha Moynihan, owner of the Pleasure Palace, the largest brothel in the old town. The next time she came in I called her by name. She laughed and made a joke about my checking up on her, then asked me to stop by to see her about a job.

I had never been to the Pleasure Palace- my income wasn’t in that category. The structure, a thick cylinder five stories high, reminded me of Bertha herself. Inside, amidst rich brightly-colored surroundings, it offered wealthy patrons of both sexes not just the services of a partner, but an amusement park of sexual fantasy augmented by holographs and somafields. All manner of drugs, from the benign to the dangerous, could be bought to dull or stimulate the senses. The Palace also served food in private dining rooms so that customers could dine romantically with their “host” or “hostess” before retiring for the evening.

Though the dining rooms remained booked solid, Bertha claimed they lost money and that the food itself was awful. (It was.) Though she realized the customers didn’t care, it made her feel cheap to sell a lousy product. I remember her blunt offer, “I want you to get this food business straightened out! I don’t expect you to make it into a place like Henri’s. I don’t even want you to, but I can’t stand the smell of that garbage they’re serving now!”

Despite my love of Henri, I couldn’t refuse the money Bertha offered. So I started work at the Palace three weeks later. The kitchen was a disaster, and straight off I fired the chef and two cooks. Nothing that could be called inventory control existed, and employees had been walking off with enormous amounts of food. I found no rational system of pricing, and the junior cooking staff seemed poorly trained and in very low spirits. After I took over, things began picking up almost at once. Indeed, it would have been hard to make them worse, but more than a year passed before

I had the kitchen running to my satisfaction.

Pleased with the results I achieved, Bertha began to give me other problems to tackle. Even in the automated 24th century, prostitutes of both sexes generally have more than their share of personal problems, and such problems often interfere with their work. Most are spendthrift; all worry about getting old and being lonely. They need someone to listen to their problems, and that was often me. If the problem seemed too serious, I recommended a psychiatrist, and Bertha usually paid the bill.

The Pleasure Palace hummed with sophisticated equipment from somafield and holograph projectors to automatic surveillance and neural neutralized that prevented the “boys and girls” from becoming occupational statistics when customer’s sadistic fantasies came on too strongly. In those days, few qualified mechanics could be found on Mammon to service such equipment, and spare parts created nightmares.

The administrative challenges of the job at the Palace kept me interested for several years. Bertha had grown tired of the hassles; I welcomed them as a chance to learn and to prove myself. Yet when I’d mastered most of them, I grew uncomfortable. Work at the brothel began to depress me. Not that I’m a prude or disapprove of sex, but the notion of people paying for something that ought to be freely shared seemed very sad. I realize that all people, even the old and not-so-nice ones, need to be touched and to satisfy their sexual desires, but people at the brothel seemed emotionally crippled. Brothels may be necessary, just as hospitals are necessary for the sick and injured, yet I’m not the sort of person who can work around either.

My years at Henri’s and Bertha’s convinced me that I enjoyed serving people, and that I like to see people enjoy themselves. I-liked the restaurant business, but I appreciated the added challenges of a more complex organization. After some thought, I decided that hotel management might offer a satisfying, lucrative career and began looking for a hotel job.

I started my new career, at a substantial cut in pay, as assistant manager in a small hotel owned by a retired transport pilot named Andy Werner. I’m sure Andy was a better pilot than hotel manager, or he wouldn’t have lived to his 100 years. His accounting records were a mess. He had a hard time keeping any staff and a harder time getting them to work when he did. Despite my inexperience- with the hotel business, I began to tackle Andy’s problems in a businesslike manner, employing the management skills my other jobs had taught me. Cash flow increased throughout the first year, and by the next year Andy showed a handsome profit and rewarded me with a bonus.

With the worst of Andy’s problems behind me, I again grew restless. I wanted to work for a really large hotel in the new city, such as the Executive or the Husaini. Only these huge establishments could provide me with a wide variety of management opportunities, and ultimately allow me to work my way up to a salary that equaled my mother’s.

Landing even a junior manager’s position at one of Hilltown’s major hotels took me the better part of a year and a great deal of politicking, including joining the Hilltown Chamber of Commerce and the Mammon Society of Hoteliers and Restaurateurs. However, my work at Andy’s had not gone unnoticed, so at long last I was offered a position as assistant night shift manager at the Hilltown Executive Hotel. The job at the Executive opened a variety of doors. At that time, it reigned as the undisputed king of hotels on Mammon, offering the most elegant appointments, the finest service, two of Hilltown’s best restaurants, and exotic, live entertainment from as far away as Earth.

During the next ten years I worked in every aspect of the business from staff management to building maintenance. As I learned more, my superiors thrust more responsibility on me, until I rose at last to general manager. By then I had become familiar with many of Mammon’s movers and shakers, and the connections I had made would serve me well in the future. Hilltown had grown enormously in that interval. As Mammon’s industrial infrastructure had grown and flourished, Mammon Mining Company had been eclipsed as the dominant economic force. The importance of rare earths in the galactic economy was turning Mammon into an important trade center not only for Humans but for every species in the Galactic Association.

My dream was to open a fully-integrated interplanetary center serving the needs of travellers not only from all of Mammon, but from all the known galaxy. The concept would provide not just a luxury hotel but a center in which travellers to Hilltown could satisfy every need. Meeting rooms, computer access, offices, restaurants, and entertainment would, of course, be included, but I also wanted a lower level with shops and service business of every kind. I began to make quiet inquiries, and it didn’t take long for me to interest one of Mammon’s wealthy builders, Anwar Shimi, in the idea. We soon negotiated a contract whereby I would join his staff and manage the design and construction of the hotel. After completion, I would remain as general manager and hold a five percent equity interest as well.

We set to work at once, securing a site near the center of town and meeting with architects. Design and construction took three years – a long time by Mammon’s standards – because of endless compromises between what I desired and what our expected revenues let us afford. Though I had many doubts, when the hotel opened, the result was everything I had hoped.

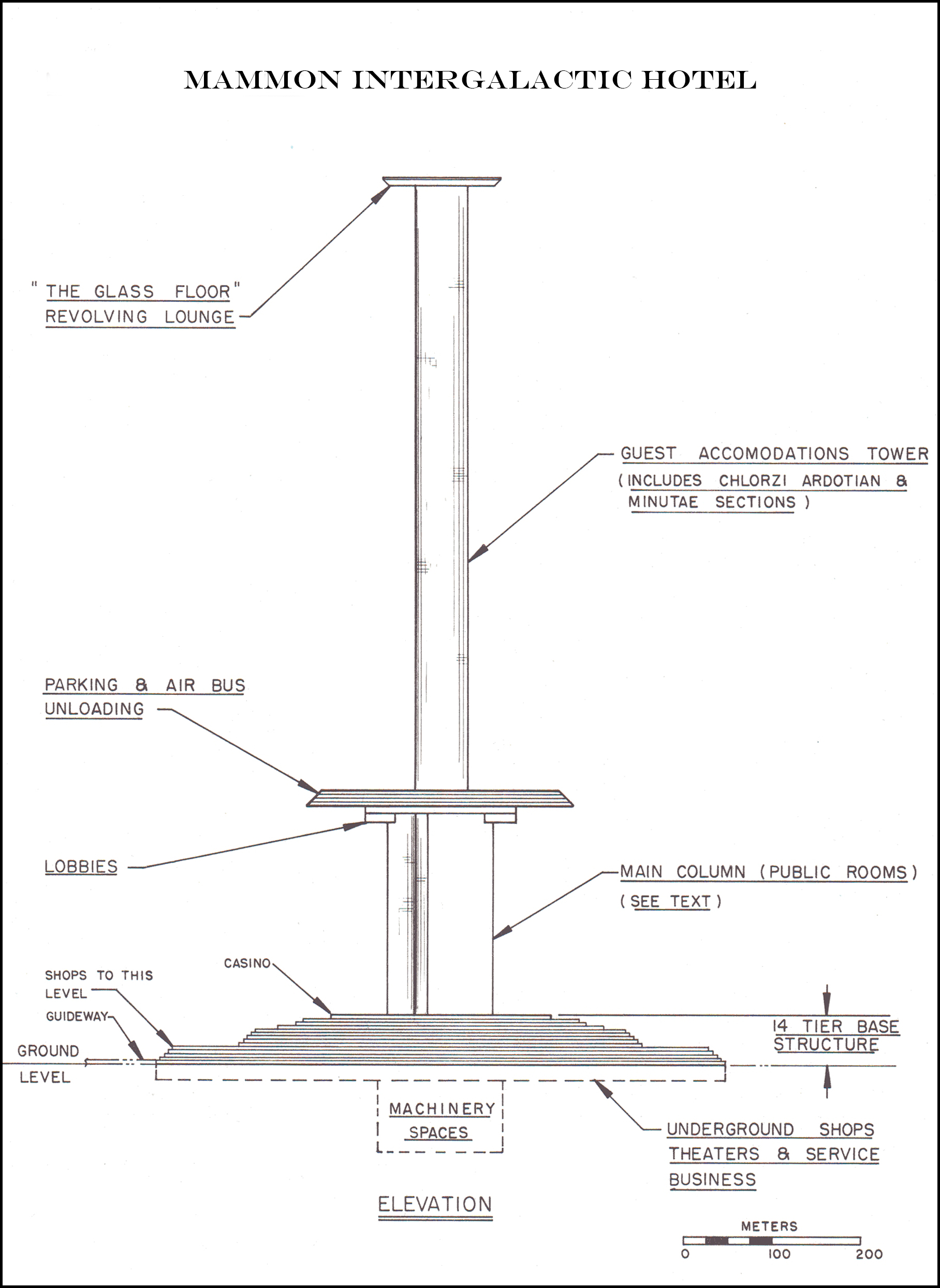

Figure 3.15 – Mammon Intergalactic Hotel

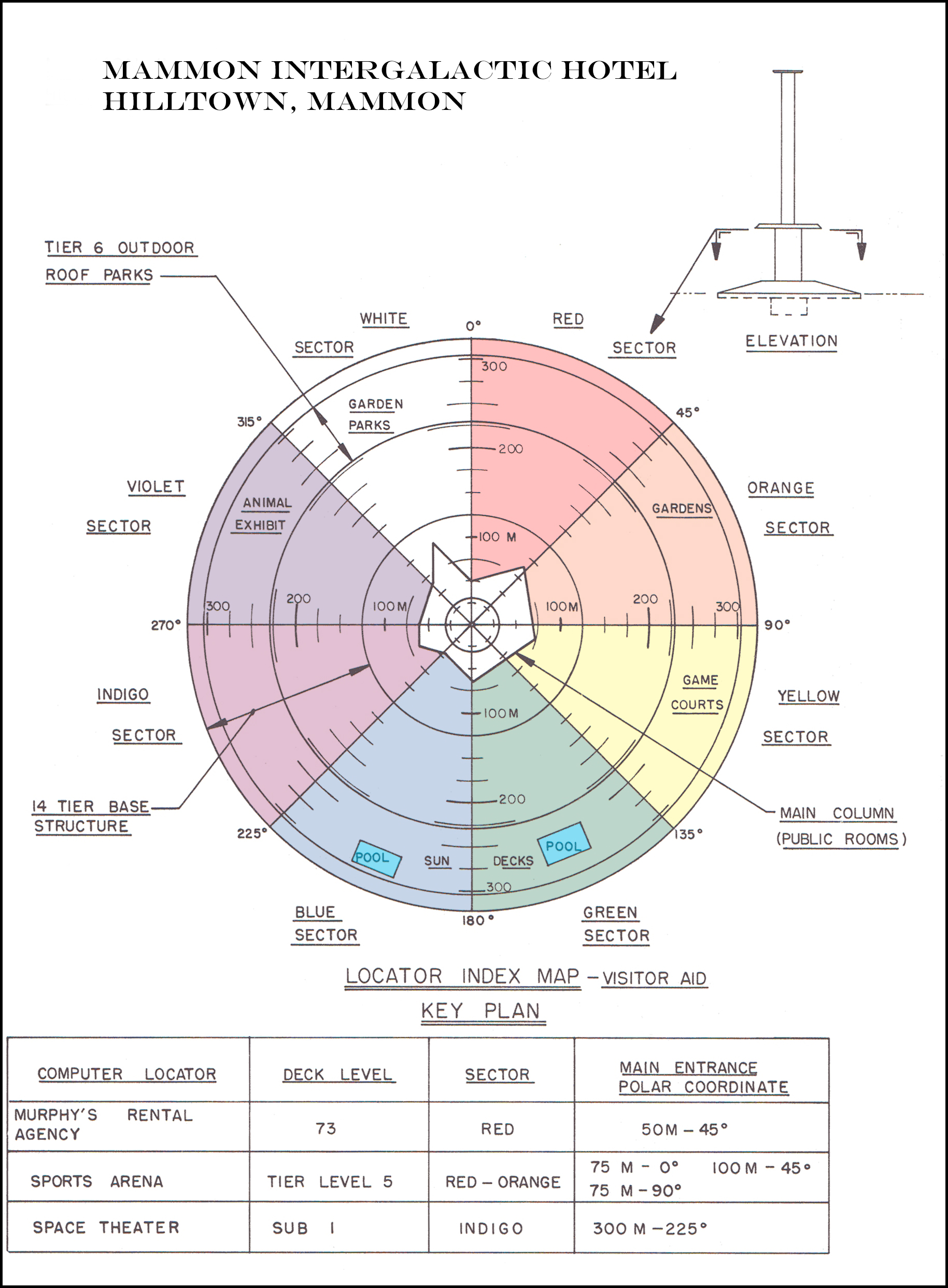

Figure 3.16.001 – Mammon Intergalactic Hotel Locator Index Map

The Mammon Intergalactic Hotel, shown in figures 3.15 and 3.16.001 above, occupies a 45 hectare site just eight kilometers from Hilltown central square. We chose a slender tower structure instead of a shorter, wider building because the tower offers more window space for its area and allows a feeling of spaciousness between the hotel and the adjacent city structures. The fourteen-tiered base structure and the subterranean spaces beneath contain about two-thirds of the building’s usable floor space and house those functions that derive no advantage from window openings. The roof above is landscaped and contains gardens, swimming pools, game courts, and a tiny zoological garden displaying interesting species of plants and animals from the other colony planets. An electrokinetic field surrounds the zoo to prevent these alien life forms from escaping into Mammon’s environment.

The lower four tiers and two subterranean levels below them contain a wide variety of shops and service businesses. Though they form an integral part of the hotel complex, I don’t attempt to manage them directly, but simply lease space to an appropriate mix of entrepreneurs that will complement the hotel’s services. An assortment of shops offers goods imported from throughout the Galactic Association. Complex appliances, specialized furniture, medical devices, and other items not manufactured on Mammon can be purchased along with forms of art from every GAIL planet. Nightclubs and theaters feature live or holographically-simulated entertainment to suit a variety of tastes, and a variety of service business from real estate brokers to travel agents serve the needs of newcomers to Hilltown. A color-coded system divides the hotel into eight sectors to prevent shoppers and guests from getting lost.

Though other colors exist within each sector, the color shown in the plan (figure 3.16.001) predominates. A low-speed guideway system transports people quickly around the shop levels, although most customers prefer to stroll and window shop.

Hotel functions begin on the fifth tier and include bars, outdoor and indoor restaurants, a convention hall, and special entertainment rooms ranging from Chlorzi armball courts to a unique exercise gym. The gym contains computer-controlled equipment to exercise selectively any muscle in the Human body. Such machines help Mammon residents condition themselves for trips to GAIL planets with higher gravity. A large casino fills the top tier of the base structure and offers a wide selection of computer-controlled games of chance. The eight-sided, irregular column rising above the casino contains a variety of public rooms, including offices, conference rooms, seven restaurants, bars and lounges and entertainment centers. A small convention hall surrounded by transparent walls occupies one entire level.

One restaurant in the column, the Amonde Room, offers diners an experience unique to all of Mammon. The Amonde serves gourmet banquets of up to 30 courses, yet diners need consume no more calories than a light snack. Meals combine real dishes mixed with simulated ones, created in the mind of the diners by a type of selective somafield. The field allows chefs to tailor diets so foods that aren’t healthful to the diners can be tasted, but need not be eaten. The process actually costs more than serving real food, but imagine what a corpulent gourmet, too long restricted to a low-fat diet will pay for an illusionary feast of Beef Wellington followed by strawberry shortcake topped with a mountain of whipped cream!

The Hotel’s lobbies lie above the public rooms, immediately below the residence towers. A unique feature of the Mammon Interglactic is its ability to cater to all member species of the Galactic Association. Of course Chlorzi, Ardotians, and Minutae comprise a small percentage of our guests, but for Mammon to continue serving as an interspecies trade and communications center, such accommodations must be provided. The largest lobby caters to Human guests, but we have arranged others to suit the need of alien species. Chlorine gas fills the Chlorzi lobby so they may breathe without respirators. The Ardotian lobby, maintained at 70° contains supplemental oxygen to provide a partial pressure of 0.9 atmospheres. The Minutae lobby fills only two cubic meters, yet can accommodate 500 Minutae!

Communications equipment forms the biggest investment in the alien lobby. A Chlorzi, for example, doesn’t just walk in and say, “I want a room.” Chlorzi communicate telepathically, not by sound. Their ideas do not resemble Human thoughts in any way. They have no concept of “I” or “want” or “room.” They cannot sense the feeble emissions of the Human brain. Special amplifiers can sense Chlorzi thoughts and computers can analyze them into elemental binary code and rebuild them into something like our language. The Chlorzi equivalent of “I want a room” appears on the desk clerk’s computer screen as “Make us of your environment,” and the clerk still needs a phrase book!

The other aliens pose different problems. Minutae voices speak in the 40 to 180 kilohertz range, yet most Human ears can’t hear above 17 kilohertz. Ardotian language consists of a complex mixture of spoken sound and physical gestures that can’t be intelligibly separated. Most Ardotians prefer to communicate with us using a keyboard of the 173 “letters” that form their written language.

Above the lobbies rise the accommodations towers containing 4,798 rooms for Humans and suitable quarters for 120 Chlorzi, 80 Ardotians, and 400 Minutae. The Human quarters, the most sumptuous in the galaxy, contain full antigrav sleep fields, five-sense full-spectrum somafields, holovision, and infinite source sound fields. Any meal, laundry, or package delivery can be accomplished instantly from each room’s transfer cabinet, and full-range data terminals link guests with the planet’s central computer. Throughout the Human lodgings, decorators chose the finest natural and synthetic materials. Real wood and natural fibers, such as Agip’s wool, have more warmth and character than any synthetics could possess.

Unfortunately the accommodations for other GAIL species cannot meet the high standards we have set for our Human guests. We have done the best job we could to create a comfortable environment for Ardotians, Chlorzi, and Minutae, one in which they can breathe their natural atmospheres, see by natural light, and relax in the company of their fellows. Yet we cannot hope to grasp the subtleties of an alien environment whose characteristics would kill a Human being within seconds. How, for example, are we to know if the “chairs” are “uncomfortable” when we’re not certain if they need to sit down or if they have a concept of “comfort”?

Even so, most aliens seem to be good sports about their first visit to Mammon and don their environmental suits for a stroll through town. Of course, the Minutae would get stepped on in the rush of Mammon’s traffic, so we arrange guided tours for them. No being in the galaxy ever saw a zoo to equal central Hilltown on a busy day!

My ramblings notwithstanding, it’s not the physical structure or the decoration but the people I meet that make the hotel business such fun for me. I enjoy sitting at the crossroads of Human history’s most dynamic society and meeting the fascinating range of beings that make it happen. Not just mining executives and engineers, but artists, builders, entertainers, lawyers, doctors, diplomats, prostitutes, scientists, con men, and religious saviors all pass through the portals of the Intergalactic. I have met hundreds of each and become friends with many, including some interesting non-Humans as well. The Chlorzi and Ardotian equivalents of “engineers” and “ship’s captains” that come to Mammon for rare earths and the diplomats who await passage to their embassies on Earth have given me unique insights into Human consciousness. Our conversations through the computer-interpreter have made me appreciate that thought can take more forms than Human minds can comprehend.

Though the hotel remains my principal interest, the visual arts run a close second. My art avocation began long ago and has grown from a hobby into a second business. Modern techniques for recording, transmitting, and reproducing information enable people on colonial worlds to appreciate Human art developed over thousands of years. But for these techniques, much of Earth’s great art would remain in musty museums on the mother planet. Yet we on the colonies have copies of paintings by Da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh, exact in every shade and brush stroke, and statues by Michaelangelo, copied to the nearest micron. Copies of such classics form a solid base of business for my gallery, but the most meaningful art must be contemporary.

Pioneering societies, like Mammon, have traditionally had little time or resources to produce artists. Not one emerged from America to rival the masters of Europe until the twentieth century. Despite our few fine local artists, Mammonites have had to reach back to Earth and to the older colonies for most of their contemporary art. Though copies of Earth’s most famous contemporary artists sell well at modest prices, people still pay extraordinary amounts to own the one artist’s original.

I’m still amazed to see discriminating art lovers pay 100 times the cost of a first-rate copy of a sculpture by a great artist, like Falcone, to have the original work of a much lesser artist. Perspective and photofilm have vanished as contemporary media. Sculpture and holographs now convey most three-dimensional concepts. Artists still make two-dimensional “wall hangers” in abstract, often textured forms. The expansion to the new worlds has greatly influenced Earth’s 24th century artists. Works inspired by the colonies seem most popular on Mammon. My favorite holograph depicts a sinister representation of Mammon as a Dante-like inferno by an artist who has obviously never been here.

Two-dimensional, original media can be shipped from as far as Poseidous, but even the lightest of sculpture remains prohibitively expensive to transport. Yet “Mammon First Copies,” computer-produced duplicates of original Earth art, bring as high a price here as the original would on the Old Planet. Like most dealers, I make my purchases from catalogs since I can’t afford the time or expense of shopping trips to Earth. All original artworks and first copies I receive bear a unique radiosignature that dates the art and prevents its exact duplication.

Recently art works from other GAIL cultures have become fashionable, particularly Ardotian geoforms and Minutian tapestries. In keeping with the intergalactic style of our hotel, I have large geoforms and several tapestries displayed prominently in the lobby. Yet I must confess, as a sincere art patron, if not the most discriminating, that I can’t imagine how any Human being can appreciate alien art. One can marvel at the intricacies of Minutian tapestries or find something pleasing in the regular patterns of the geoforms, but this is no more art to us than the pleasure we might get from enlarging a drawing of a starship’s lacy, web-like structure and hanging it on the wall! Art ought to convey the artist’s feelings to the viewer, but we can never expect to fathom the emotions of our alien associates in space exploration.

The artifacts of alien culture, the import of goods from other worlds, and the foreign travelers who come and go give evidence of the fact that Mammonites have become part of a transgalactic society. As such we are sensitive to the criticisms levied against us on other planets. We have been accused of being too materialistic and hedonistic, of being too interested in physical pleasures and unconcerned with spiritual ones. Doomsayers prophesy that such ways will lead to social decay, crime, and the ultimate destruction of our society. I acknowledge that Mammonites do concern themselves with material well-being, that we spend a great deal of money gratifying our physical pleasures. Yet throughout Human history, people have sought relief from toil and the wherewithal to appreciate the sensuous aspects of life. On Mammon, we are simply fortunate enough to have these things. Not since the 20th century, when the tiny oil-rich nations of Arabia controlled half the world’s petroleum, has so small a group of people been endowed with such wealth from the ground.

Yet like the ancient Arabs, the wealth of Mammonites is vulnerable too. Just as breakthroughs in nuclear, solar, and coal technology greatly decreased the Earth’s dependence on petroleum, so could a technical breakthrough in matter/ antimatter technology eliminate the need for rare earths.

I, for one, do not fault people here for enjoying their wealth. We have earned it; literally everyone on Mammon works hard for a living. Little inherited wealth exists, certainly not the sort that characterized ancient monarchies and the early industrial revolution. Mammonites have not grown complacent. Within a century, our industry will satisfy all our material needs. Far from degenerating into a crime-infested society, most people on Mammon value work and personal independence. If we lack enough concern for religion and philosophy, perhaps that’s because we are a young society.

The opportunities to become rich attracted most of our immigrant population. Now that we have achieved our physical desires, I fully expect the next century to bring accelerated intellectual development. Few of Humanity’s great philosophers worked fourteen hours per day. Most had ample leisure in which to indulge their thoughts.

I see parallels between the development of Mammon’s society and my own personal life. As a young man, I was interested mainly in money and my narrow technical career. As I matured, I began to appreciate other aspects of life. Personal relationships became important to me. As I rose through the management hierarchy, I began to take a broader view of its purposes. I no longer thought just in terms of how to serve food or fix machinery, but of what motivates people, and how to establish a “permanent” institution that would benefit not only shareholders and employees, but our world’s society. I began to view business problems in the context of Human desires, instead of the reverse.

Today I reflect a great deal about the purposes of life. What ought we to be doing with our lives? Human history has been a continual struggle over scant resources and an endless battle with nature. In the process, Humans did great harm to each other, more than natural disasters ever did. Now we stand at the beginning of an age in which our struggle with physical need has been won. We have food, shelter, leisure, and diversions in abundance for all. We have learned to live in peace with not just each other but with alien beings from other star systems as well.

Where do we go from here? What shall be our purpose in living? I can’t answer these questions, but when I was young I wouldn’t have asked them. I hope to spend more time in the future reading the works of other Humans and aliens who have addressed these questions. I hope I shall find answers, if not for all Humankind, then for myself.