Many potential pioneers ask if intelligent life has been encountered on habitable exoplanets. The answer, by definition, is no. GAIL’s strict non-interference policy precludes this, although the colonies of Yom and Romulus come closest to being exceptions.

The similarities between the colonial worlds and Earth are interesting, but their differences ignite the imagination. Each habitable exoplanet is a world unto itself, diverse in geography, life forms, scenery, and climate. Each has its swamps, deserts, forests, grasslands, mountain ranges, and fertile valleys. Each has enough land to satisfy the needs of today’s colonists, future immigrants, and their descendants for dozens of generations.

Yet the greatest contrast between the colonies and the Earth springs from the pioneers’ lifestyles. Today, 15 billion souls pack the Earth, and as a poet wrote so long ago, not one of them is an island. Eighty percent of the world’s population crowds into megapolises stretching for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of kilometers, and very little of the Earth’s prime land is left unoccupied.

In contrast, the colonies are vast empty worlds. One statistic illustrates the difference: The most densely populated exoplanet colony, Poseidous, has a population density of only 2.1 people per square kilometer, compared to the Earth’s population density of more than 101 people per square kilometer! Colony cities are manageable, numbering in most cases less than a million people. As on Earth, the cities serve as centers for commerce, manufacturing, and trade, but it takes only minutes to zip out of them into the open countryside. Cities can afford the luxury of open space within their borders and crime and pollution are almost unknown.

The crowding and the age of Earth’s societies have also crippled individual activity. Great bureaucracies and political power structures control most economic and social life. Forms of government vary from state to state, but certain patterns are universal. No building can take place in urban areas, no business enterprise can be started or expanded, and no drastic changes can be made in any activity without securing a myriad of permissions from governments and from one’s neighbors.

Such regulations are a necessary evil of life in a crowded world, yet these necessary evils have spawned stagnation and corruption. Favoritism, politics, and prejudice too often play the major role in determining who will be permitted to undertake an activity and who will not.

In contrast, colonial land is so plentiful and colonial needs so great that few controls are necessary or possible. Population growth is welcomed not discouraged, for there is much to be done and few hands to do it. In every enterprise from basic industries to the arts, innovation rather than regulation is encouraged. Bureaucrats, managers, and a class of idle rich don’t fit in well where almost everyone must be willing to roll up their sleeves and do manual as well as intellectual labor. Some people still primarily organize while other primarily carry out specific tasks, but class distinctions between these groups are not as pronounced in the colonies as on 24th century Earth.

Earth is wealthier than the colonies. It has more factories, facilities, consumer goods, and luxuries even on a per capita basis than any of the colonial worlds. Most Earth residents can retire at some age between 60 and 80 and live the remainder of their 120 to 150 years engaging in leisure pursuits. Yet such wealth means little where no virgin forests survive, no air is unpolluted, and crowds fill every desirable place.

Pioneers on exoplanet colonies own fewer consumer conveniences, fewer luxuries, and most of them work past the age of 100. Yet a colonial family can have a five-hectare spread of land with trees and fields, perhaps even a lake or beach, for their personal retreat. Families can develop their own 400-hectare farm and raise not only food for sale but grow fresh fruits and vegetables for their table that cannot be equaled on Earth. Colonial craftsmen build genuine wooden furniture, an art lost centuries ago on Earth. Natural materials- wool, silk, and leather-supplement factory synthetics.

These items can scarcely be had on Earth at any price. The Earth is a planet of conveniences. No one must perform the drudgery of manual labor. Machines move earth, harvest crops, lift and carry, assemble machinery, weld and fabricate, and take care of domestic chores like cooking and cleaning.

On exoplanet colonies, machines are in short supply. Many assembly operations must be performed by hand until machines can be built to do them. People build vehicles, electronic equipment, and structures by hand, aided by simple cranes and lifting tools. Many farmers must clear their land with manual disintegrators and plow with manual power-assist drives. Personal robots are non-existent in many colonies and semi-automated cooking and cleaning are part of the daily chores. Many pioneers find these manual tasks satisfying and challenging. Some even choose to return to a totally natural life, making all of their clothing on simple hand-operated machines and growing their own food using natural methods. Yet no pioneering society has ever delayed making automated equipment to do manual labor, and most pioneers strive to create Earthlike levels of convenience as soon as possible.

FOOD

Colonial food differs little from food on Earth. Few colonies possess native staple grains containing the appropriate food value and sufficiently high yield per hectare for a modern society. On Earth, selective breeding techniques developed over five centuries have produced grains with high yields, resistance to disease, the ability to withstand climatic extremes, and high food value per unit weight. Therefore, most colonies have imported the seeds of basic food crops such as rice, corn, wheat, soy, barley, kelp, and hybrid algae, and all use the latest agricultural and aquacultural techniques. Similarly, colonists raise highly specialized domestic animals. Dairy cattle, pigs, sheep, trout, shrimp, and halibut comprise the most common species.

After several generations, the older colonies have turned to the adaptation of native plants and animals for food. The same selective breeding techniques used on Earth have been applied to produce desirable food qualities in species native to the colonies. The new foods usually lend themselves to new culinary methods, and the older colonies have already created unique cuisines that impress the most discriminating of Earthly gourmets.

MEDICINE

The quality of medical service on the colonies equals that of Earth, but is not so widely distributed geographically. A fully-equipped hospital capable of treating or curing all Earthly ailments forms an essential part of the equipment brought by the first colonists, and GAILE constantly updates medical information in the colonies’ central computers. As colonies grow, medical facilities become more widely disbursed. Most colonies, though, find it more expedient to concentrate hospitals that specialize in sophisticated techniques such as organ rejuvenation and cancer cure in the central cities. Rapid transportation is available to carry people in need of such treatments from the planet’s remotest outposts. Pioneers who live far from the cities generally learn more first aid than the average Earth person so they can cope with emergencies until help arrives.

The cost of medical care is provided in a variety of ways on various colonies, but only Genesis and Poseidous employ any sort of socialized medicine. Doctors generally provide medical services on a contract basis; for a monthly fee, all medical care is provided. This practice encourages frequent check-ups and early diagnosis. The same automated techniques for daily and weekly monitoring of body functions commonplace on Earth are available on the colonial planets, but individual families do not often have their own personal somascanners.

In general, medicine is of less concern to pioneers than it is to Earth people, although doctors are always welcome and needed. Colonists seem to be much healthier than people on Earth. Medical researchers speculate that three factors may account for this. First, immigrants start out healthy. Few of the chronically ill attempt to make the trip. Second, colonial diets contain fewer highly-refined foods, since refined food production requires both more raw food and processing machinery.

Lastly, many doctors believe that many real physiological illnesses are psychosomatic in origin. Pioneers tend to be busier and happier than Earth people, and, as such, have no psychological reason to become sick.

EDUCATION

Education has always been of great importance to pioneers on every colony. Indeed the foundation of the colonial program rests upon Humanity’s desire to expand its knowledge, and to educate itself about the universe and the planets on which we live. Though pioneers find that every day they learn a great many things about their world, their jobs, and themselves, formal education is also important to both children and adults. More than 50 percent of the adults who emigrate to the colonies ultimately find themselves pursuing a job, trade, or profession different from the one they pursued on Earth. Conversely, pioneers consider it extremely important to educate their children not only about their new world but about the Human race and its long, difficult history. Pioneers know they must not forget Earth’s past, lest they make the same mistakes that were made on Earth.

COMMUNICATIONS

For centuries, any person on Earth has been able to converse at will with any other person anywhere on the globe through various forms of electronic communications equipment. All such equipment employs some form of electromagnetic radiation to transmit the message. All electromagnetic radiation travels through space with the speed of light, yet even at this speed, a sentence would take years to reach even the nearest of the colony planets. This fact of physics makes conversation between pioneers and Earth residents impossible. Instead, colonists must record messages by voice or writing which ships or space probes then carry to Earth. (See Interstellar Transportation and Communication for details.) Although pioneers can continue to communicate with Earth, most of them quickly form new relationships on their new home planets.

INTERPLANETARY TRAVEL

Except for starship crew members, few people ever make a round trip between Earth and the colonies. Few are wealthy enough to afford the great cost of such a trip merely for a vacation. Occasionally, Earth’s government will appropriate funds for a prominent scientist or government official to make a round trip, and about one percent of those accepted for the GAILE sponsored emigration program find they cannot tolerate life on the new planet and return home. The GAILE screening process insures high probability that every pioneer will adjust to his new world, but no method of selecting people for anything is perfect. Those who can’t adjust are repatriated and GAILE attempts to secure them a job and to return a portion of their Earthly assets. However, potential colonists should recognize that GAILE does not take these actions lightly, and few who decide to abandon their new life ever recover fully the income, assets, and opportunities they gave up on Earth to make the trip.

MONETARY SYSTEMS

Colonial monetary systems differ little in form from the money of Earth. Records of financial credits are maintained in computer accounts and transferred as obligations are incurred. Only two of the colonies, Genesis and Romulus, rely on the planetary government to control the monetary system. The rest of the colonies maintain several privately operated exchange systems.

As there is so little trade between the colonies and Earth, there is little convertibility between Earth and colonial monies. It is very difficult for a rich person to emigrate to one of the colonies with much of his wealth since the securities and property he owns on Earth have little or no value to the colonists. A wealthy person can liquidate his Earthly wealth, buy capital equipment, valuable to the colony, and pay GAILE for his passage and the cost of transporting the equipment. Few have ever opted for this course, but one notable exception, Luigi Albertino, son of a wealthy industrialist, designed the first toroidal reflux plasma fusion reactor and could not get a permit to operate it on Earth. He had the prototype plant shipped to Brobdingnag, where power was greatly needed. There he operated the plant as a highly successful private enterprise.

Most pioneers find themselves quite penniless when they arrive on their new worlds, but they soon rectify this situation. New arrivals live in the temporary housing afforded by the ship’s spires (see Interstellar Transportation and Communication) and are given an advance to purchase basic necessities until they find employment. Within a few days of arrival, most immigrants find work, the advance is repaid, and they begin to accumulate property.

LAND CLAIMS

On most colonies, unoccupied land can be claimed by anyone, but colonial governments set limits on the amount any person can claim for a specific purpose. For example, one cannot generally claim 1000 hectares for a personal residence, but one can claim that amount for a farm or mining site. To maintain a claim, the land must be developed for the specified purpose. Claimed land usually becomes available again if undeveloped within a specified period. As long as the land remains under development it may be sold. Most urban land falls in this category.

GOVERNMENT SYSTEMS

Governments play far less important roles in the lives of pioneers than they do in the lives of Earth people. The colonies field no standing armies and police forces are small by Earth standards. The existence of nation-states and their struggles for land have been the traditional causes of war throughout Earth’s history. All colonies, except Poseidous, have global governments subordinated by regional and local governments of various kinds. Also, the planets are big enough for their small populations to have all the land they want. Thus, the two principle causes of war do not exist. Furthermore, the high mobility and ease of communication between all pioneers on each planet, makes it unlikely that separate, competing nationstates will ever arise.

CRIME

The same reasons that reduce the chances of war on the colonies also reduce individual violence. By Earth standards, the colonies exhibit low per capita incidence of theft, fraud, murder, and assault. Yet in any Human society, some individuals prefer to violate others’ rights rather than work honestly to satisfy their wants. Consequently, most of the colonies maintain investigative bureaus to assist local crime-fighting organizations. These bureaus primarily combat organized crime and large-scale fraud. The central computer bureaus maintain their own force of detectives to combat computer crimes.

Colonies have fewer laws to break than Earth. “Victimless” crimes such as drug abuse, homosexuality, thought crime and sedition infract no colonial statutes, a fact that alleviates much of the burden of law enforcement agencies. Rights to property, freedom of speech and assembly, and the rights to travel, worship, transact business, and choose one’s legal guardian are guaranteed by the colonial constitutions.

INTERPLANETARY WAR

Prospective pioneers often ask about the possibility of interplanetary war. No planet under the protection of the Galactic Association has had to worry about invasion from space since GAIL was founded. Even so, the possibility exists that one day GAIL will encounter a technologically advanced, yet hostile race. The chances of that happening are greatest for colonies on the outer reaches of Association explored space.

While the remotest colonies make no specific provision for interstellar war, each has some line of defense. Every colony possesses at least two orbiting space stations. These are used primarily for observing the planet’s weather, map making, mineral surveying, relaying communications, and scientific experimentation. The stations also serve as astronomical observatories, scanning and mapping nearby space and studying the planet’s sun.

While performing these functions they act as early warning systems for the approach of starships and can identify non-Association ships. The stations are equipped with w-field disintegrators (see Interstellar Transportation and Communication) to protect them from meteors. These w-field beams are effective weapons in the event of attack. Should a gang of extortionists try to seize a station and turn the beam on the planet, the stations can be disabled from the planetary surface.

POLLUTION

The problems of pollution which have concerned Earth’s governments for centuries pose little problem for colonial governments at present. In the colonies, the most modern of Earth’s technology is employed as a starting point, and most industries are therefore pollution-free. In their cities, pioneers leave open spaces for parks, so that future generations will have the open space they need.

LANGUAGE

All but two of the colonies speak Standard International English, or a slight variation of it. SIE is often criticized as cumbersome and difficult to learn, but it is understood, if even rudimentarily, by most of the people on Earth. Consequently, early pioneers drawn from all over the Earth had to use SIE to communicate with each other.

Poseiduous and Genesis are the exceptions to this rule. Because a large percentage of southern Asians numbered among Poseidous’ early pioneers, Poseidons developed a unique dialect known as <a id=”Sinoenglish”></a>. On Genesis, the planned and idealistic nature of the society led founders to adopt Esperanto, an ancient Earth language specifically designed during the national period to be an international tongue.

Anthropologists and linguists speculate that someday colonies will evolve their own planetary languages. In fact, every colony more than fifty years old has already evolved native words which make ordinary conversation confusing to newcomers. Yet experts doubt the languages of the colonies will ever become totally alien. An interdependence of worlds exists, like the interdependence of continents on Earth. As long as frequent communications remain necessary, languages cannot become too diverse.

The following sections describe each of the planet colonies. Each section contains a map, a data table, a brief description by the GAILE staff of the planet’s physical and social characteristics, and an account of life on the planet by a resident chosen for his or her broad knowledge of the planet’s life and lifestyles.

MAPS AND TIME CONVENTIONS

A number of conventions to aid the Earthbound reader have been incorporated into every section. All planet maps are drawn so that their rotation proceeds from left to right. The top of the map is by definition the north pole and the bottom the south, regardless of the polarity of the planet’s magnetic field. On Genesis and Poseidous, place names have been converted from native spellings to SIE equivalents to facilitate pronunciation and the accounts by residents have been converted to SIE. As the data tables show, each planet has a different year and day. Consequently, all colonies have developed their own calendar and time scale, different from the 12-month, 24-hour convention used on Earth. Most colonial time is based on “hours, minutes, and seconds” in multiples of eight or ten. To avoid confusing Earth readers, all references to time have been converted to their equivalents in Earth Standard Time and dates have been converted to the Gregorian calendar.

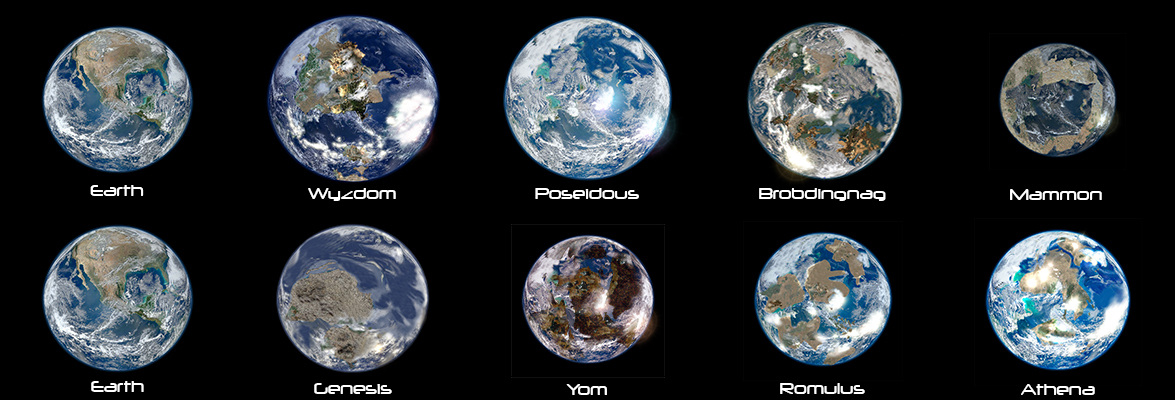

Figure 3.1.002 – Exoplanets Similar to Earth

Figure 3.1.002 – Exoplanets Similar to Earth

The composite photograph above shows the planet colonies view from space and the size of the planet relative to the size of the Earth. For a table of planets physical data comparisons to Earth, please click the link below named LIFE ON THE PLANETS.