August 25, 2016

This week the news media boiled over with the most significant exoplanet discovery since the first one was confirmed in 1992.[1] A team of astronomers with the European Southern Observatory (ESO) working with the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) on the 3.6-meter telescope at the La Silla observatory in Chile discovered a rocky planet orbiting in the habitable zone of Proxima Centauri, the smallest of three stars in the Alpha Centauri system.[2]

Alpha Centauri is the closest star system to earth’s sun. It consists of three stars, commonly called A, B, and Proxima (or C).

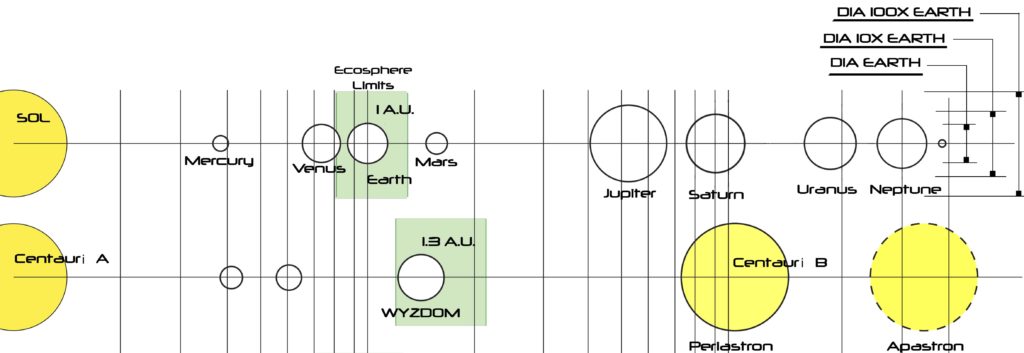

Alpha Centauri A and B orbit each other at a distance that varies from 11.2 to 35.6 astronomical units, about the same distances that Saturn and Neptune, respectively, orbit Earth’s sun. (One AU is the distance from the Earth to the sun.) Proxima orbits the two larger stars at a distance of about 15,000 AU.

Proxima is a red dwarf star whose mass is only 12 percent of Earth’s sun. At about 3,050 degrees K, it is much cooler than the sun, whose effective temperature is 5777 degrees K. Because of Proxima’s small size and low temperature, the habitable zone surrounding it is much closer to the star than that of A and B. (The zone is defined as one in which liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface.)

The newly discovered planet, dubbed Proxima b, is only about 0.05 AU from Proxima and requires only 11.2 Earth days to orbit it. At such a close distance, astronomers believe the planet’s day would be equal to its year, so that one side of the planet would always face the star and the other the blackness of space. On such a planet, the sunny side would probably become too hot and the dark side to cold for liquid water to actually exist. Moreover, the planet’s close orbit to the star would make the sunny side susceptible to strong ultraviolet and x-ray radiation and the effects of stellar flares, both of which are destructive to Earth-like life. For more discussion, see “The Habitability of Proxima Centauri b.”

In their enthusiasm for the new find, the discoverers of Proxima b dismiss these problems. “Tidal locking does not preclude a stable atmosphere via global atmospheric circulation and heat redistribution.”[3] To support this claim, the astronomers cite a murky paper by a group of geophysicists published in February 2016 that says the habitable zone surrounding red dwarf stars might not be where simple calculations suggest.[4]

In the original Handbook for Space Pioneers, the planet Wyzdom was postulated to orbit the A star because it is most like Earth’s sun in mass, assumed age, and radiation. These properties would place its habitable zone about one AU from the star, giving it a year and seasons not too different from Earth’s.

The planet Wyzdom is supposed to be 14 percent larger in diameter than Earth and its mass is about one-and-a-half times Earth’s assuming its density is similar. Coincidentally, the estimated mass of Proxima b is a minimum of 1.3 times Earth,[5] making it about the same size as Wyzdom.

Whether a planet like Wyzdom orbits Alpha Centauri A or B has yet to be determined. Habitable planets are too small compared with the masses of larger stars to permit detection by the radial-velocity methods available today. In the future, more sensitive HARPS-like instruments or different exploratory methods will settle these and other questions.

Computer simulations performed by physicists at the University of Padua and an astronomer from the Cote d’Azur observatory in Nice in 2002 showed that the formation of terrestrial-sized planets around Alpha Centauri A is possible. However, in some of the simulations, the planets formed became unstable after 200 million years, not long enough for life to evolve.[6] The discovery of Proxima Centauri b seems likely to rekindle interest in these types of studies.

Whether or not liquid water and free oxygen exist on Proxima’s newly discovered planet, it does not seem like a world most people would want to settle. In the absence of a reasonable day and night cycle, the only habitable places would likely be in the twilight zone between the light and dark sides. Such a planet would seem unlikely to support food sources or the kind of cultural diversity that would make settling exoplanets fun.

Nevertheless, the discoveries by the ESO’s HARPS team deserve high admiration. Operating on a modest budget from an earth-bound observatory, these astronomers have discovered exoplanets in several of our nearest stellar neighbors. They have also demonstrated that no huge planets occupy the habitable zones of other GAIL Earth candidate star systems.(See the update “Three Companions for Poseidous” for an example.) These observations leave open the possibility of smaller Earth-sized planets in these nearby systems.

[1] “A planetary system around the millisecond pulsar PSR1257 + 12” by A. WOLSZCZAN & D. A. FRAIL published in Nature no. 355, 145 – 147 (09 January 1992)

[2] “A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around

Proxima Centauri” by Guillem Anglada-Escudé et. al. published in Nature no. 536, 437–440 (25 August 2016), accepted 7 July 2016.

[3] ibid. p5

[4] “The Inner Edge of the Habitable Zone for Synchronously Rotating Planets Around Low-Mass Stars Using General Circulation Models” by Ravi Kumar Kopparapu et. al. published in Astrophysical Journal 16 February 2016

[5] Anglada-Escudé op. cit. p 1

[6] “Formation of terrestrial planets in close binary systems: the case of α Centauri A” by M. Barbieri et. al. published in Astronomy and Astrophysics no. 396 6 September 2002.